IntroductionThe Ripper or Repper family of Cornwall has a history that goes back over 500 years and 20 generations. Movement around Cornwall was common in the 16th to 18th centuries and branches of the family developed in other Cornish towns and villages such as Redruth, Stithians, St Austell, Helston, Padstow, Cubert, Perranzabuloe and Nort Hill as well as on the Lizard peninsula. The earliest known migrant from Cornwall was in the late 18th century when Alexander Repper travelled to London as part of the Cornish militia and stayed there. Some of the family left their native Cornwall to live in other parts of Britain, other parts of the English speaking world and even in Brazil and Mexico. There are farmers, miners of tin, coal and gold, hairdressers, chimney sweeps, gardeners and paupers. There are scientists, teachers, adventurers and soldiers. Cornish archived records, like many across Britain, have significant gaps where registers and papers have failed to survive the rigours of time. The gaps which occur at the time of the English Civil War in the mid 17th century make the creation of a family line difficult. The Ripper family tree has been compiled by use a wide range of sources including parish registers, civil registration, probate documents, leases, court rolls, taxation documents, letters and many other surviving records.

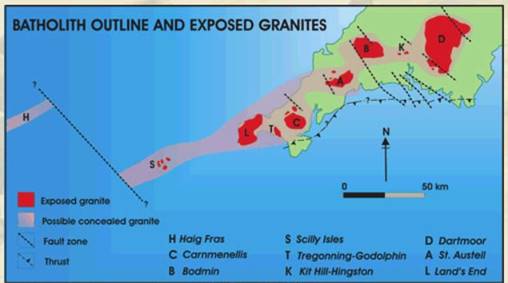

Occupations Penwith, the extreme west of CornwallCornwall is a peninsular surrounded on three sides by the Atlantic Ocean. The warm North Atlantic Drift current supplies a bountiful variety and number of fish and other sea creatures around its shores. The climate is temperate. Whilst snow is not unknown it is often restricted to the highest and bleakest moorlands and is uncommon in the warmer sheltered parts of West Cornwall. This enables the growth of even sub-tropical plants such as hardy palms. The soils are fertile in places but much of the land is occupied by the moors of Cornwall which are suitable only for rough grazing. 300 million years ago a mass of molten rock pushed up from below the Earth’s crust, underneath what is now South West England. You can imagine the animation below is looking westwards from Dartmoor in the foreground to Bodmin Moor in the distance. You will see the molten rock break into the crust, cool down and suffer erosion to expose the granite uplands we see today. The animation looks into the future when the surface has been further eroded to show the single mass of granite (a batholith) that extends from Dartmoor and onto Bodmin Moor; from there it ranges down through the county to Land’s End and beyond. Granite contains many minerals and in its molten state spreads out into surrounding rocks creating seams of metal ore, essentially copper and tin. |

The Formation of Cornwall's Moors |

Granite intrusions in Cornwall and Devon |

|

Fishing and the SeaBreage's proximity to the sea and the actions of its earlier residents earned it a fearsome reputation with seamen as can be evidenced from the following: God keep us from rocks and shelving sands,

We have no evidence that any of the Ripper family members were ever involved in anything significantly underhand in the manner of smuggling, wrecking or even imaginative beachcombing. This however, does not mean that they weren't. In 1749 it was recorded at Gulval that "We have had the greatest floods of rain ... in any man's remembrance ... many thousand tynners by this means deprived of employ and starving". In these circumstances who would not resist any means to keep oneself and one's family alive and well? Traditionally the Cornishman is also associated with fishing for his living, particularly seine fishing for pilchards. Although not far from the coast, fishing has not been a significant occupation in the Ripper family.

Mining

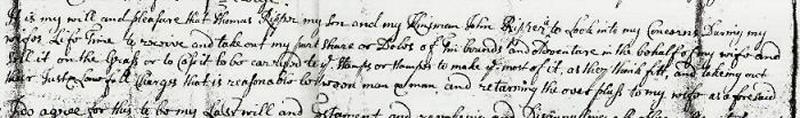

Daniel Ripper (1655-1725), for instance, had inherited his father's interest in Polladras Mine which had been in the family for generations. His son William Ripper went to live in North Hill and died there; the inventory of William's estate recorded a continued interest in the mining activities back in Breage. In his will written in 1725 Daniel Ripper wrote: "It is my will and pleasure that Thomas Ripper my son and my kinsman John Ripper is to look into my concerns during my wife's lifetime to receive and take out my part share or doles of tin bounds and adventure in the behalf of my wife and sell it on the grass or to cause it to be carried to the stamps to make the most of it as they think fit, and taking out their just and lawful charges that is reasonable between man and man and retaining the overplus to my wife as aforesaid." |

Extract from Daniel Ripper's will, 1725 |

The price of metals in the world markets has always had a major influence on the Cornish, and Breage's, economy and the last major downturn was in the period leading up to 1877. This caused many Cornishmen to follow their earlier cousins to emigrate from Cornwall to find work. Many travelled the vast distances throughout the world where mining was still thriving. The destinations for the Ripper family descendants were the coalfields of northern England, the goldfields of South Australia, the mines around Lake Michigan in the USA and the mines in Mexico.

|

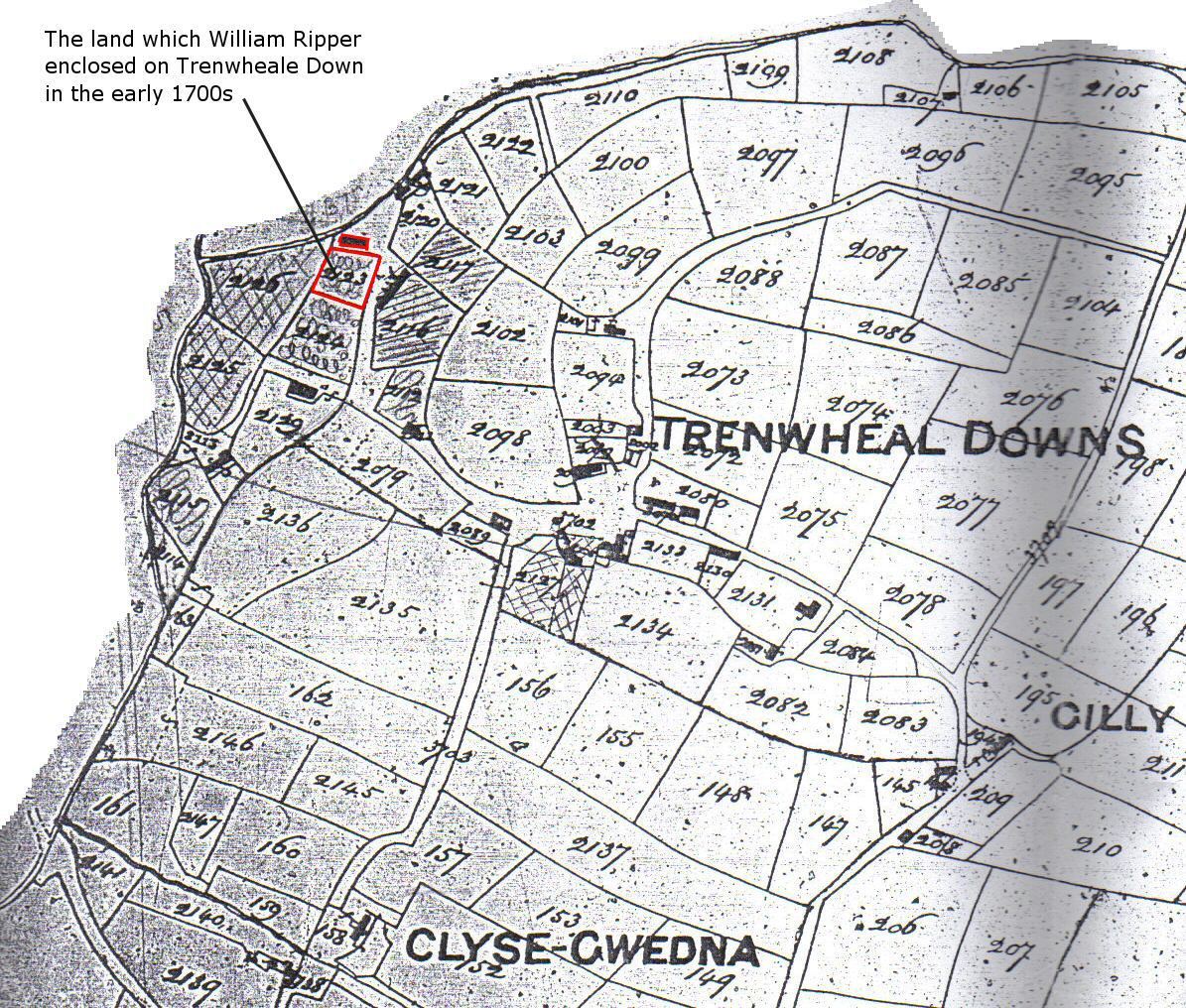

Farming Fields around Breage ChurchtownJohn Leland's view of Cornwall in the early sixteenth century was of an uneven landscape of rich cultivated land and barren wasteland. The amount of corn grown, for instance, was inadequate to meet the needs of the county and much was imported from other counties. Carew, in his survey, thought that the Cornish had neglected husbandry in favour of tin mining, but when the mines began to fail and the population continued to increase they were constrained to return to agriculture and had since become very proficient in it. Techniques to improve the land were developed and Cornwall became well known for such ideas. They used sand from beaches to help lighten the consistency of the soil in the fields. Carew reports the use of 'ore-weed' to improve land for barley production. In the early seventeenth century Cornwall was principally a pastoral county, particularly in the Eastern parishes around Bodmin Moor. Quantities of wool were produced but the economy was more mixed with arable and dairy farming constituting the major contribution. The quality of the soil and shelter from the Atlantic weather lessened further east in the county and farming there adjusted accordingly. Few farmers in the western counties could afford to specialize in a single form of husbandry and a range of livestock would be kept including sheep, pigs and poultry. Cows were less common in Western Cornwall as providers of milk because of the sparse pasture and goats would have been kept for dairy produce. By the 1600s much of the land had been enclosed, in the manner shown in the map above, and there was an increasing cultivation of what had previously been waste land. Wheat was grown where conditions allowed. Two types of wheat were planted, a bearded variety on the better soils and 'knotweed' with a lower yield on the poorer land. Hardier corn crops such as oats and barley and rye were also cultivated. Between 1712 and 1727 William Repper is accredited with enclosing a parcel of land on Trenwheal Downs shown on the tithe map below. It is possible his brother John had already enclosed land on Trenwheal Downs. In a lease of 1780 it is described as: All that messuage or dwelling house heretofore built by William Repper deceased with the garden thereunto belonging ... and late in the possession of Elizabeth Repper deceased but now of the said Benjamin Thomas all of which were formally hedged or inclosed in by the said William Repper deceased out of Trenwheale Downs and is part and parcel of the Manor of Godolphin." |

The enclosure of Trenwheal Downs |

|

MigrationFrom these early times, branches of the family moved to other parts of West Cornwall. They set up homes in places such as Gulval, Redruth, Helston, St Agnes, Crowan and on the Lizard peninsula. Then, from the late 1700s and up to the twentieth century branches of the family spread their way across the English speaking world. For many this was caused by the downturn in the Cornish economy at the time. For centuries Cornwall had depended upon the export of tin and other ores to provide its income. With the discovery and exploitation of new deposits in Australia and North America the price of these metals fell and the ensuing hardship for Cornish miners prompted many of them to migrate to the new lands. It has been said that if you go the bottom of the deepest mines on Earth you will find a Cornishman there. Failures of potato and corn harvests in Cornwall in the 1840s resulted in significant price increases which led to severe hardship of the working population. Foreign competition, ironically assisted by the recruited pick of the best Cornish miners, brought about a mining recession and large numbers of mine closures. The copper mining industry virtually collapsed in 1866. Many left Cornwall to escape these hardships as well as reasons such as the payments of tithes, rates and taxes. The political situation and religious intolerance also encouraged emigration. During the exodus of the 1870s the number of miners in Cornwall decreased by about a third and a further third in the 1880s. The usual destinations were the mining areas in North America, Mexico, South America, Australia and South Africa. |

The family has not produced any notable public figures but this does not detract from its interest, at least to living members of the family. The members of the family presently number over 16,000 people across the ages and their lives reflect the social conditions of the times.

The family has not produced any notable public figures but this does not detract from its interest, at least to living members of the family. The members of the family presently number over 16,000 people across the ages and their lives reflect the social conditions of the times. Mining in Cornwall goes back into the mists of time and was a source of supply of tin for the ancient Phoenicians. The provision of food from farming must, of necessity, have developed even before mining for tin, copper, zinc and other metals. The largest mine in the Breage district was Wheal Vor, shown here, which was active from the early 1600s into the 20th century. This was the first Cornish mine to have a steam pumping engine and in the 1841 census employed almost 1,200 people with many others dependent upon its success. There are many family members on the tree who are shown as miners. There are also family members who owned shares in tin and copper mines and became adventurers.

Mining in Cornwall goes back into the mists of time and was a source of supply of tin for the ancient Phoenicians. The provision of food from farming must, of necessity, have developed even before mining for tin, copper, zinc and other metals. The largest mine in the Breage district was Wheal Vor, shown here, which was active from the early 1600s into the 20th century. This was the first Cornish mine to have a steam pumping engine and in the 1841 census employed almost 1,200 people with many others dependent upon its success. There are many family members on the tree who are shown as miners. There are also family members who owned shares in tin and copper mines and became adventurers.