Sergeant, 88th of Foot, The Connaught Rangers

|

Rogerstown |

|

John Connor was born in Rogerstown, Drogheda in |

|

Army Service |

|

|

24 Oct 1839 |

Enlisted as a labourer from Meath, being paid 1/1d

(one shilling and one old penny) per day from that date |

|

1 Jan 1840 to 31 Mar 1840 |

Absent from general muster whilst in |

|

15 Apr 1840 |

Muster book shows him as absent without pay, but

no ensuing disciplinary action is recorded, such as loss of pay |

|

4 Oct 1847 |

Awarded good conduct badge |

|

9 Apr 1848 |

Promoted to corporal |

|

25 Oct 1849 |

Awarded second good conduct badge |

|

4 Apr 1854 |

Embarked with service companies for |

|

10 May 1854 |

Promoted to sergeant |

|

5 November 1854 |

|

|

6 November 1854 |

Surgeon's report states that his ring finger on

his left hand was amputated |

|

10 July 1855 |

Discharged |

|

Enlistment |

||

|

John enlisted in At the time he was 5' 8½" tall, had

grey eyes, brown hair and was of pale complexion. The pay and muster books

record that he was paid a bounty on enlistment of £3 17s 6d and the

recruiting sergeant received 18s 6d. |

|

|

|

|

They also record his occupation as a baker of At the time of his enlistment the Connaught

Rangers were stationed at Richmond Barracks, |

|

|

|

|

|

During this time John was selected as one of a

group men under Corporal William Joyce escorting William Duddy, a deserter of

the 64th Regiment from His colleagues were Private Michael Barry, Private

Stephen German (who replaced Private John Grace at the last minute) and

Private Jerome or Heron. Their part was the 4 day march from John went absent without leave (AWOL) on the 11th

and 12th May 1840 for which he was deducted two days pay but no other

disciplinary action seems to have been taken |

|

|

The incidence of AWOL seems high in the records

and appears to be tolerated. In the third quarter of 1840 he was stopped two

day’s pay whilst he was on board ship. The reason for him being on

board ship has not been specified. For 34 days in the months of October and November

1840 John was in General Hospital but the cause of this is not known. |

|

|

|

|||

|

Shortly after he was released from hospital the

regiment left |

|

||

|

In |

|||

|

|

For the whole of 1841 and 1842 John was shown as

being with the regiment. There are some occasional absences explained by

hospital interment and guard duties. During most of 1843 he is shown on detachment for

unspecified reasons. This continues until March 1844 when he is shown in

hospital again. |

|

|

|

On March 18th he left |

|||

|

|

|

The 88th left |

|

|

|

John Connor next appears in the records on October

3, 1844 at the Depot Battalion in Voucher No.52, to cover the expense of "one

man from John moved from |

|

|

|||

|

John and the Depot Battalion of the Connaught

Rangers found themselves returning to their Irish homeland at the start of

the Great Potato Famine and they did not leave again until the end of the

famine was in sight. As soldiers of the British Army their usual diet

was meagre, although during the years of the famine this food must have been

welcome when compared with the hardships their parents and families were

suffering. Standard daily rations consisted of a pound of bread, eaten at

breakfast with coffee, and three quarters of a pound of meat, boiled for a

midday meal in large cookhouse coppers. The 88th spent their first year in Boyle, Co

Roscommon and, during this time, John was detached to A writer in the United Service Gazette a few years

later says of the Connaught Rangers of this period: |

|||

|

"Perhaps the

whole world does not furnish a more striking instance of the influence of

military discipline upon the Irish character than is supplied in the gallant

88th, the Connaught Rangers. The regiment is

composed entirely of Irishmen recruited for the most part in the |

Bringing

out the dead during the Potato Famine |

||

|

It is a fact of

which the glorious 88th may be proud, as it is of the laurels so gloriously

earned in the Perhaps these comments should also be viewed in

light of the famine as |

|||

|

|

Birr was possibly where John met his future wife,

the widow Anne (Robinson) Melsop. Anne’s first husband, Thomas Melsop was in

the 16th Lancers and he may have been killed during the Sikh Wars of

1845-1846. Widows of men killed in action received no support but were

expected to rely on charity – widows’ pensions were not

introduced until the time of the Boer War, around 1900. On October 4th 1847 John was awarded his first

Good Conduct Badge and an extra penny a day in his pay. |

||

|

Sometime later during the same October the Depot

Battalion moved from Birr to Tralee, Co Kerry, and Anne Melsop must have gone

with them. On 30th October 1847 there is a marriage by licence

at Tralee Registrar's Office of a Private John Connor (son of Richard Connor,

a carpenter) of the 88th Regiment (bachelor of full age) resident at Tralee

Barracks to Anne Mellsop (widow, servant) living at Well Lane, Tralee in Co

Kerry. Her father is given as John Robinson, a trader. The marriage was

witnessed by Margaret O'Sullivan and Patrick Sullivan. It appears from later research that John was Roman

Catholic and Anne was Protestant which may have been the reason for the

Registry Office marriage. According to the pay and muster rolls John Connor

was promoted to Corporal on April 9, 1848. |

|

||

|

John’s firstborn son, Richard Connor, was

born in On October 20, 1849 John Connor was awarded his

second Good Conduct Badge and a second increase of one penny a day – he

then received 2d. per day extra. As a Corporal, John’s basic salary

would be 1s.6d. per day plus the two Good Conduct Pays of 1d. each. The Depot

Battalion remained in Tralee until April 1850 when they moved to Castlebar

where they remained until the end of the year and then left Whilst in Castlebar, John and Anne had a second

son, whom they named John and he was baptized at the Catholic Church on May

10, 1850. Unfortunately, young John must have died at an early age as the

couple named another son John a few years later. |

|||

|

The Kerry Recruit |

|

|

At the age of nineteen, I was

diggin' the land Chorus: To me Kerry-I-Ah, fa lal deral lay, So I buttered me brogues and shook hands with me spade Then up came a captain, a man of great fame, Well the first thing they gave me it was a red coat The next thing they gave me they called it a horse The next thing they gave me, they

called it a gun, |

The next place they took us was down to the sea, We reached We whipped them at All dyin' and bleedin' I lay on the ground, But a surgeon come up and he soon staunched the blood, Now that was the story my

grandfather told, |

|

|

||

|

The first six months of 1851 were spent in Bury, Lancashire,

after which the battalion moved to During the period 1851-1854, the regiment moved

extensively around the south of In

February 1853 the regiment went off to Haslar and |

|

|

|

The regiment returned to Bury on August 20, 1853,

taking the train from The immediate political background to the Crimean

War can be traced to November 30, 1853, when the Russians destroyed the

Turkish fleet at the Black Sea Military preparations began which directly

concerned the Rangers towards the latter part of 1853, and in February 1854

it was intimated that the 88th would be included in an expedition then being

organized for the John was with one of the two detached companies in

Stockport, On March 28th war with |

||

|

The Niagara off |

At John embarked on the Cunard steamer Niagara with

the Service Companies (entire battalion) at noon on April 4, 1854 and set

sail for the The Niagara reached |

|

|

Leaving Malta the same night the 88th landed at

Scutari, opposite Constantinople (now Istanbul), on the 19th and took up

their quarters in the Turkish barracks, a large building that would

subsequently become famous as the hospital where Florence Nightingale and her

nurses tended the wounded and those who fell ill from rampant disease. John

was to be an inmate of Scutari, as we shall see later. |

||

|

|

||

|

The 88th joined forces with the 77th and 95th and

became known as the "Yellow Brigade", all three regiments having

yellow facings on the uniforms. They shifted out of the barracks into tent camps

to make room for more incoming regiments from On May 10th, Corporal John Connor was promoted to

Sergeant. On May 29th the regiment embarked on the Cambria

for The tent allowance was one tent for every fourteen

men and the men’s kit (in knapsacks) was ordered to be reduced to a few

necessities only. "The remaining

articles," wrote Colonel Stevens in an early history of the

88th "were left behind in those most useless of

inventions, the squad-bags, which were confided to the care of a rascal at

Pera, and were, I believe, never seen again: at least I never got back the

articles which I left in his charge." |

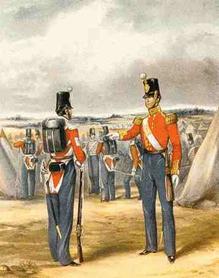

Connaught Rangers in uniform of the time of the

Crimean war |

|

|

Later, we shall see John’s discharge papers

show he claimed for lost kit – at least we know what happened to it. |

||

|

On June 1st the regiment was at The days in The boredom came to a halt with the first outbreak

of cholera on July 23rd. From then on their camping ground was frequently

changed in the hope of counteracting the epidemic but the cholera spread

throughout the Allied army and continued during the rest of the summer and

autumn. The situation of the war changed at this time and

the Allied forces were ordered to return to the Crimea from Between the end of July and the time they set sail

the 88th had forty-nine deaths from cholera, two from fever and many men were

left behind in hospital in Many of the horror stories reported in the popular

press of the day stem from the time that followed this landing back in the A writer recorded a description of the Connaught

Ranger’s and John’s first night ashore which reads: "This, our

first experiment of lying down to sleep in the open air can never be

forgotten. The officers had no baggage beyond such as each could carry, and

the knapsacks of the men having been left on board the Orient each man had

only a shirt and a pair of boots wrapped in one blanket, with three

days’ rations of salt-pork and biscuit. It rained heavily all night and

was extremely cold. As only grass and furze could be obtained no fires would

burn more than a few minutes, thus nothing could be cooked and the few

articles the men had brought were soaked." |

||

|

The |

Six days later was the They immediately marched towards Sebastopol as

siege operations had become necessary and they pitched camp near John and his colleagues were still sleeping in the

open until October 4th when an officer managed to obtain tents for the

division from |

|

|

"Our days

passed very much alike: after being under arms before daylight (exceedingly

cold work), the remainder of the day, when off duty, was passed as best we

could in camp visits or trips to |

||

|

Sometime during this month John sent his wife,

Annie, another £1 from his pay. John spent the rest of his time on

12-hour day or night sentry duties in the trenches or as a member of one of

the working parties who were constructing a twenty-one gun battery in

preparation for the Siege of Sebastopol. |

||

|

The |

|

The first bombardment lasted six days until

October 25th when an attack by the Russian army brought on the Battle of Balaklava

in which the 88th, as a unit, was not involved. It was here that, through an

error in the transmission of orders, the light cavalry brigade under Lord

Cardigan charged massed Russian artillery in that most famous of all cavalry

charges – The Charge of the Light Brigade. Also at |

|

The |

||

|

The next day, the 26th, John saw action repulsing the

Russians in the first Battle of Inkerman but the battles of the 25th and 26th

were only preliminaries to an event vastly more serious. The great Battle of

Inkerman, or "the Soldier's The battle raged for almost the whole day, and was

prosecuted in thick fog, heavy undergrowth, and with little if any

generalship being shown on either side. As dusk fell, the British held the

field (having received useful, if belated, help from the French). The numbers

of the Russian dead left on the field exceeded the numbers of Allied troops

that had been attacked. The Battle of Inkerman was fought on November 5th

and Sergeant John Connor was shot in the ring finger of his left hand. It

appears from the records that John’s finger was amputated by surgeons

at the battlefield. |

Cannonballs

pepper the battlefield at Inkerman |

|

|

Removing

the wounded at Inkerman |

The surgeon's report (WO116/64)

gives this detail: ·

John Connor, Sergeant 88th Foot, age 34 ·

Place of Birth - Rogerstown, ·

Occupation - baker ·

Rate of pension - 1 shilling and sixpence

per day ·

Foreign service - 3 years in ·

Character - Good with 2 good conduct

increments and no recorded offences ·

Surgeon's remarks - amputation of ring

finger of left hand after gunshot wound at Inkerman |

|

|

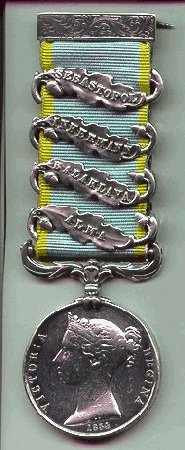

The Inkerman clasp was awarded to all those who were

present on the battlefield, including many who were never engaged. On hearing

of the selection criteria for the various clasps, at least one infantry

officer railed at the powers that be for granting him a Balaklava clasp,

which he felt belonged to the cavalry alone, and granting the cavalry, who

never came under fire at Inkerman, the clasp for the latter battle, in which

over 17,500 men (mostly infantry, and mostly Russian) were killed or wounded. |

||

|

Scutari |

|

|

On November 7th John was sent to the hospital at

Scutari, arriving on November 10th, where he remained until January 10th. Scutari is where Florence Nightingale started her

reforms of the nursing profession and hospital standards. She was there at

the time of John’s treatment and it is possible that he saw her during

his stay. Considering the horrendous standards of the time it’s

surprising that he survived his treatment in Scutari and did not succumb like

so many others. Figures show that the death rate in the |

|

|

We must remember that John and the men of the 88th

had had no change of clothing since mid-September when they left their

knapsacks on the Orient. Their clothing and boots were constantly wet and

infested with vermin and when the Orient finally arrived at Due to much skill, and underhand deals, their

Colonel and their Quartermaster obtained tents, rations and cooking pots

which alleviated some of the suffering. Cholera, diarrhoea and frostbite

were, however, prevalent and scurvy appeared by the spring of 1855 as the

soldiers’ diet consisted entirely of salt meat. Despite bloody victories over the Russians on the

River Alma and at the Battles of Balaklava and Inkerman, the war dragged on,

as the Russians refused to accept the allies' peace terms. Finally, on

September 9 1855, John was luckier than many and was sent home by

troopship on January 10th 1855, whilst the rest of the regiment was preparing

for the main Siege of Sebastopol. |

|

|

Discharge |

||

|

After John’s arrival in |

|

|

|

|

John was formally discharged from the Connaught

Rangers, at His discharge papers show some notes about pay discrepancies

during the course of the Crimean War and he also claimed for the loss of his

kit which, as shown above, was stored and ransacked at the start of the war. |

|

|

He was discharged aged 34 years and 4 months old

as a sergeant (trade as a baker) standing 5' 8½" tall. He is

shown as having no distinguishing marks, despite being declared unfit for

service following the amputation of a finger on his left hand, having served

15 years 260 days. He served 8 years as a private, 6 years as a

corporal and 343 days as a sergeant, earning 2 good conduct medals. John

Connor may have been awarded the Crimea Medal (an example of which is shown

here) with two clasps for Alma and Inkerman. Following his injury he was not

present at Pension records for mid-1855 showed John Connor on the list of pensioners with a Kilmainham admission number of #1897. |

||

|

There was a repeat of his medical record and he

was awarded a disability pension of 1s.6d. per day. The space where the pensioner’s

place of residence could be recorded was left blank. |

||

|

|

|

Twins were born to John and Anne and baptised

Edward Inkerman Connor and Mary Anne Alma Connor on March 3, 1856 at St

Mary’s Catholic Church, Drogheda, On 10th May 1858 at St Peter's A Joseph was baptised in John and Anne were to have at least seven children

– Richard (1848), John (1850), Lawrence Patrick (about 1854), twins

Edward Inkerman & Mary Anne Alma (1856), another John (1858) and Joseph

(1860). The last four children were all baptised in Drogheda, Co The notes on John’s records are confusing as

they show pension increments dated 1881 but, according to the marriage

certificate of his son, Richard, John was deceased by 1876. Although the

payments might have been to John’s widow this seems unlikely

considering the fact the widows’ pensions were not introduced until

around 1900. As yet the record of John’s death has not been found. |

|

This biography is a joint effort. The collaboration

of Kathleen Andersen, Teresa Ripper & Ken Ripper has brought this

biography into existence. |