|

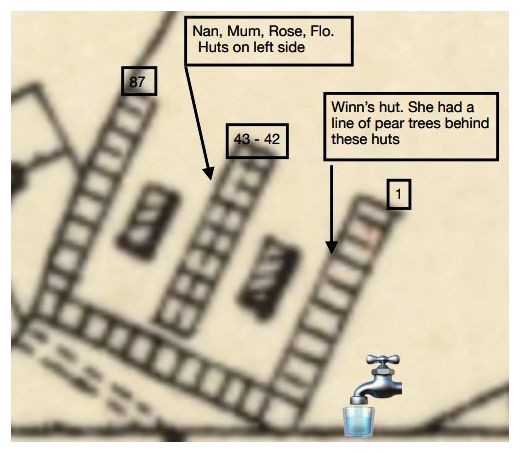

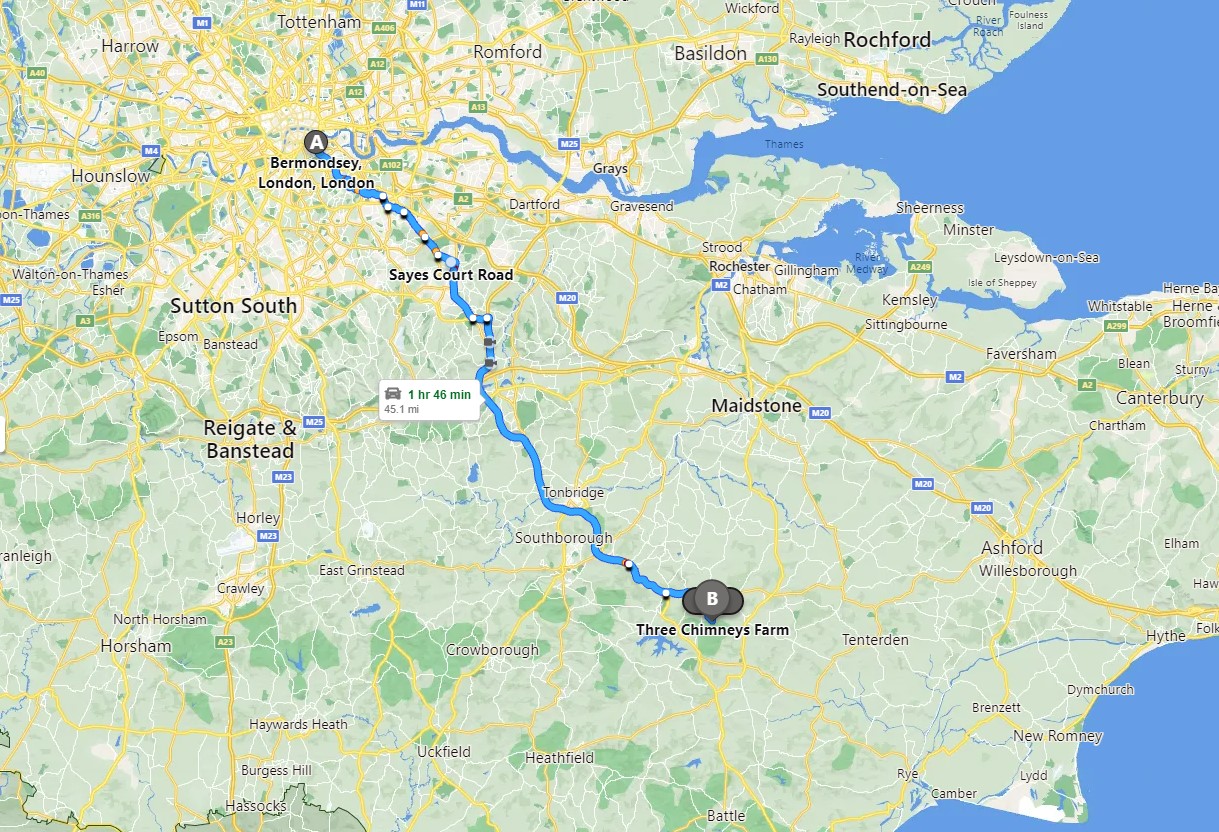

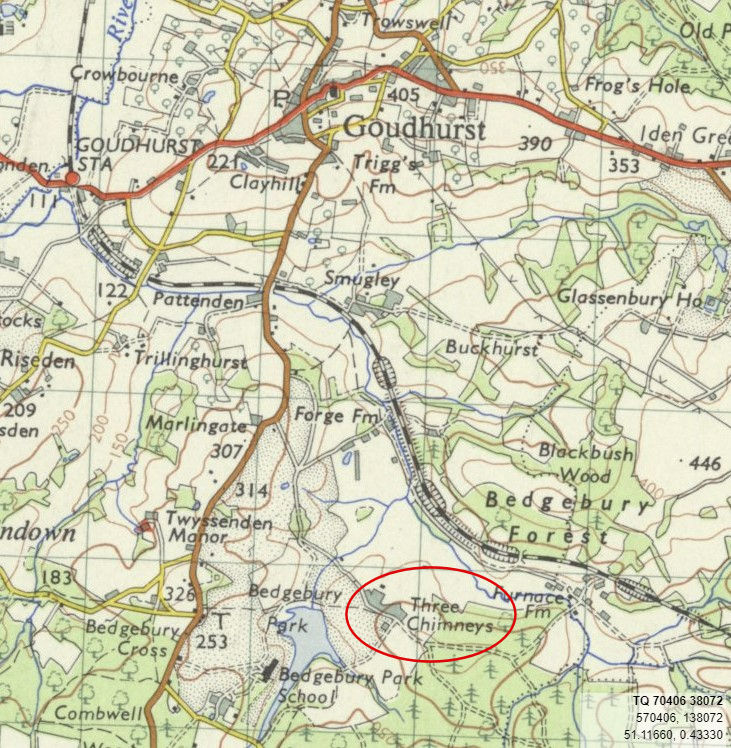

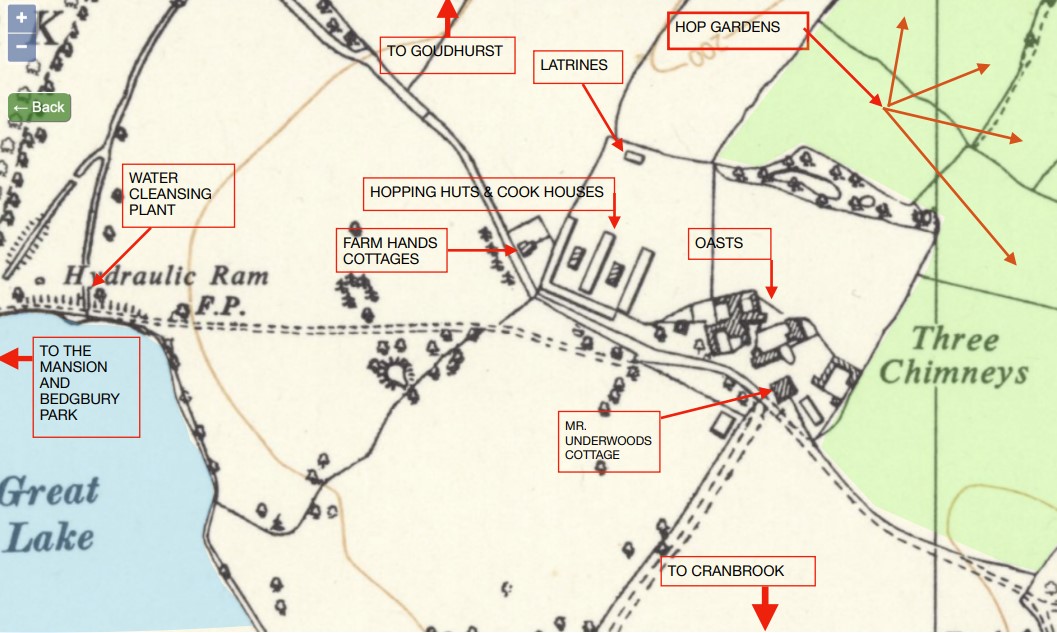

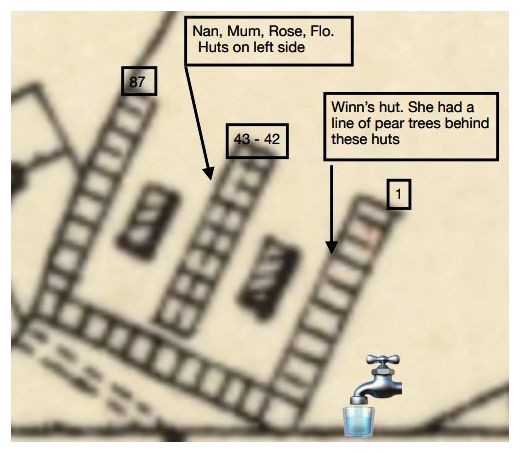

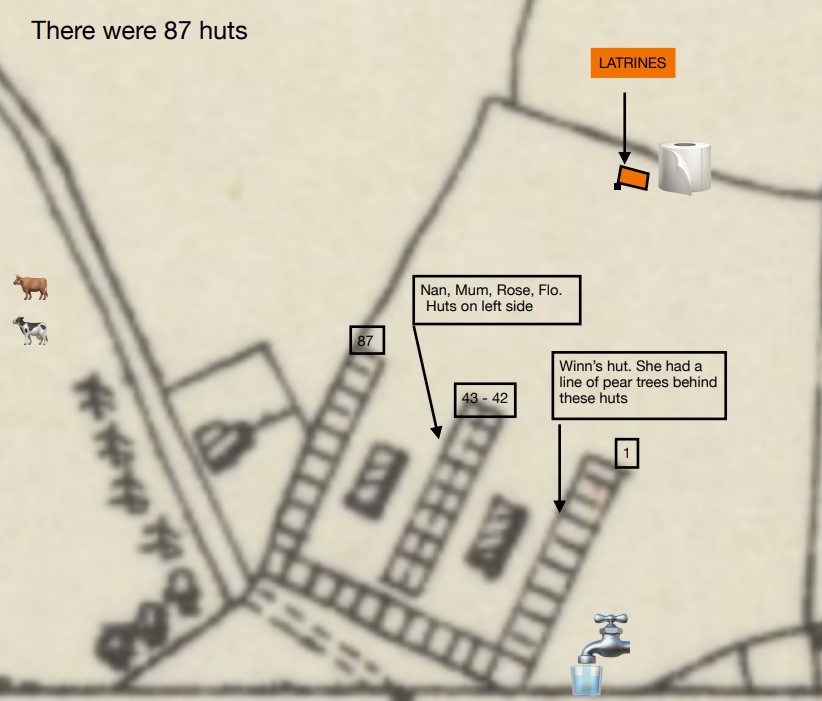

Three Chimneys Farm had 87 or huts for most of the hop pickers; others were accommodated in a barn that had been made habitable to a basic standard. The huts were considered superior to those on many other farms as they were brick built.  The huts were arranged as an 'E' shape with a centrally placed cookhouse for each half of the 'E', as shown on this plan; click for a lerger image. The huts were arranged as an 'E' shape with a centrally placed cookhouse for each half of the 'E', as shown on this plan; click for a lerger image.

The Ripper family occupied three or four huts - numbers 44 (Nan Ripper), 45 (Mary Ripper) and 47 (Florrie Martin) in the centre block. Rose Ripper may have been 43, 46 or 48 but from this distance in time this is uncertain. In the eastern block was number 5 where Aunt Winnie and her brood stayed. Billy recalls that the Barnes family lived at number 1, "Aunt Kate" ( no relation at all) was at number 2 and the Gillettes at number 3 or 4; these were Bermondsey families and near neighbours who lived on or nearby to Vauban Estate, Spa Road, as did Bill and Mary Ripper.

This photo shows huts numbered from 84 to 87; click for a lerger image. More images of the huts can be seen in the Gallery section on this page This photo shows huts numbered from 84 to 87; click for a lerger image. More images of the huts can be seen in the Gallery section on this page

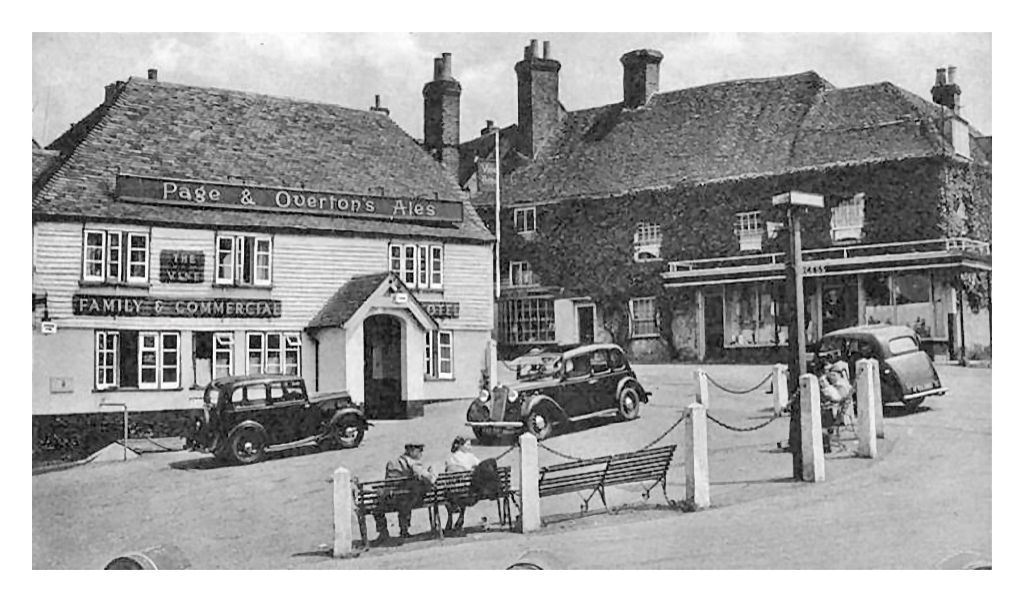

Each hut was a square single room, about 10 feet by 10 feet, with a corrugated iron roof, a sliding barn door that could be padlocked, whitewashed walls and one small window; it was furnished with just a single bedframe that took up more than half of the available room. The huts were intended for sleeping and occasional shelter; the rest of the time people would spend outside either working, cooking, washing or relaxing. Indeed, when the pickers took time outside at the pub in Goudhurst, even then they sat outside on the wall of what is now the car park. Hopping wasn't an 'indoor' experience.

Other furniture, cooking implements and accessories were brought from home as described above and transported either on the train or on lorries with the pickers, as shown in the image above. Some people brought rolls of wallpaper to pin to the walls to make the hut more homely; the wallpaper would be unpinned at the end of the picking season, taken home and brought back in the next year. The wheels were taken off the cart which was then used as a cupboard. Regular attendeees that had spare furniture and who were guaranteed to return in the following year could leave items of furniture in their hut, but this was usually no more than a mirror and a small chest of drawers.

Each hut would accommodate a family, or, if it was a large family, part of one. Winnie's hut, for instance, would accommodate her own family of at least six at any one time; sometimes more. Nan and Florrie could have similar numbers in with them. With such large numbers the bed in each of the huts was well occupied - some of us at one end, some at the other.

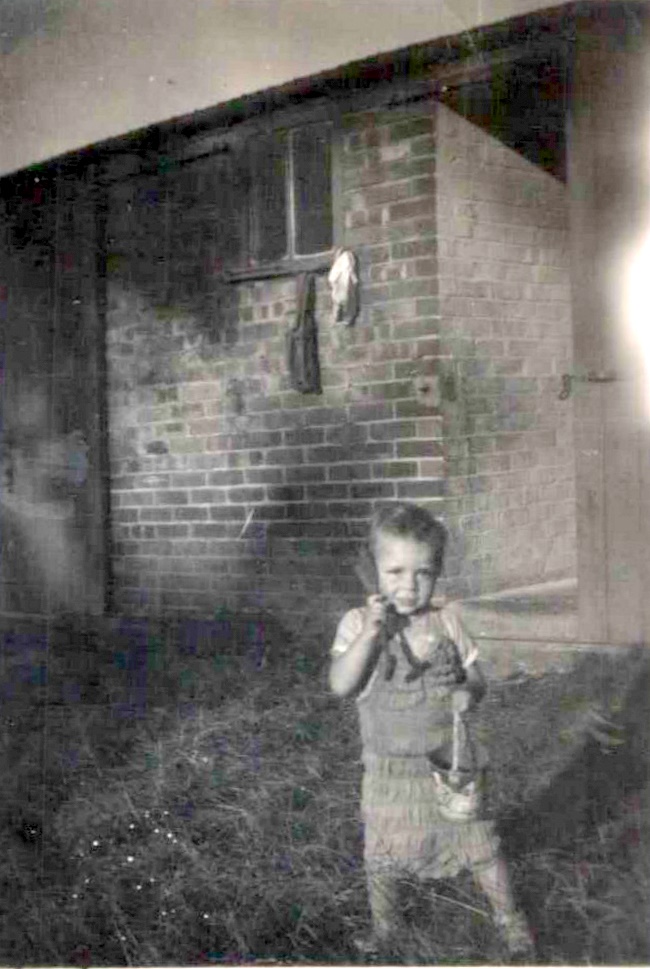

Upon arrival it was necessary to clean the hut and make the bed. For a mattress, each bed had a palliasse. This was large fabric bag stuffed with straw. On the day of arrival it was usual for a tractor loaded with straw to drop off a bale of straw at each hut. Ken recalls that around 1953 or 1954, probably the last time he went hopping, the children were sent to stuff the palliasses with straw that had been stored in the high numbered huts (about 84 to 87). From this supply each palliasse was filled and taken into its hut and rested on the bedframe. Billy remembers that once you got used to them, the beds would be warm and comfortable.

The huts had no running water, no electricity, no heating or any toilet facilities, except perhaps a bucket, jug and basin brought by the occupying family. Some families had chamber pots but with our large numbers, we substituted this with a bucket. Some families had chamber pots but with our large numbers, we substituted this with a bucket.

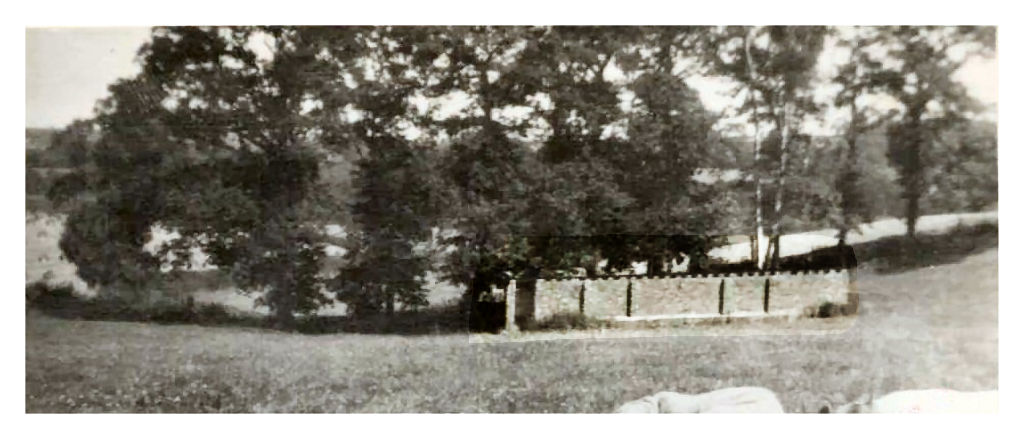

The latrines (pictured here) were well away from the huts, a 30 feet long brick building separated in the middle for male and female. The toilet was a long seat suspended over a deep hole. The smell was dreadful. Lime was occasionally thrown in the hole. Women rarely used the latrines, they used to go in twos or threes to the woods with a shovel.

Water was carried from the standpipe, shown on the above plan, by bucket (a different bucket!) to the cookhouse or the hut according to need. Given the number of people in each hut, washing wasn't necessarily a very private practice. The men would often wash and shave on the grass outside their hut, using a mirror temporarily hung on a nail on the door.

Lighting and warmth was usually sourced from a primus lamp and/or a paraffin heater. The heaters were rarely lit, but after dark the hissing primus lamps attracted vast numbers of moths and other insects.

To get provisions was a 2 mile walk with the pram to Goudhurst. Next to the oast was a hut where you could get some things on credit which came off your final earnings. Each hut had an account book in which the bill for articles was recorded and signed for; this book was kept by the vendor. There were always traders coming around the hop gardens while you were working selling bread, cakes, sweets, clothes, shoes, soap, jewellery, fruit and all manner of things. A regular was an Indian man with a suitcase from which he sold brightly coloured silk ties.

There were four cook houses. They were square blocks with a chimney serving four separate fires. From the time of arrival the farmhands would unload faggots they brought on tractors for feeding the fire as the stockpile was burnt away. Each fire had iron rungs to hang the pots over the fire. When people started bringing paraffin cooking stoves, the cookhouses were used mainly for boiling water. The fires would be maintained by the older, more responsible children throughout the day.

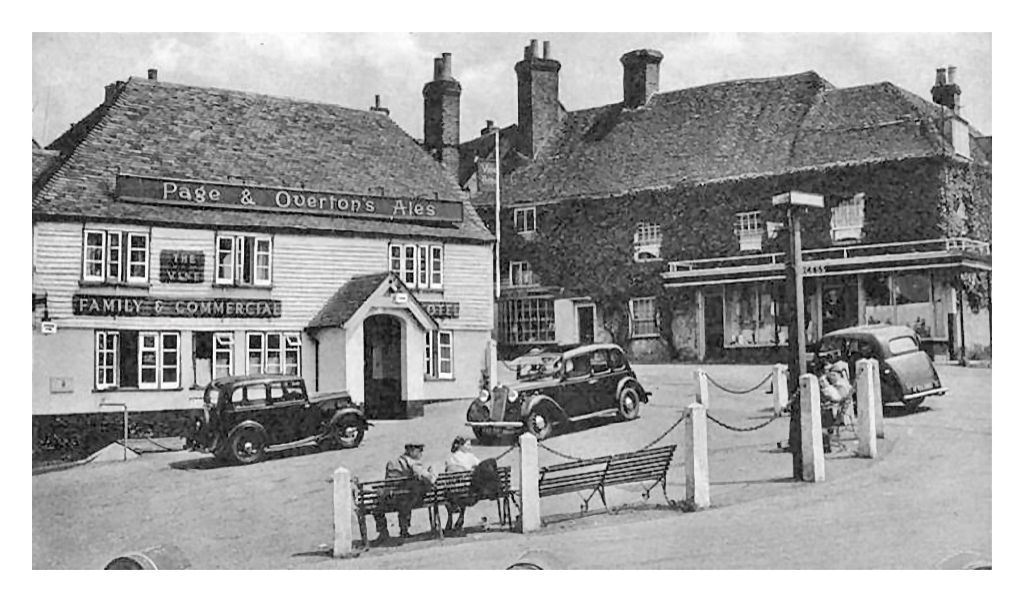

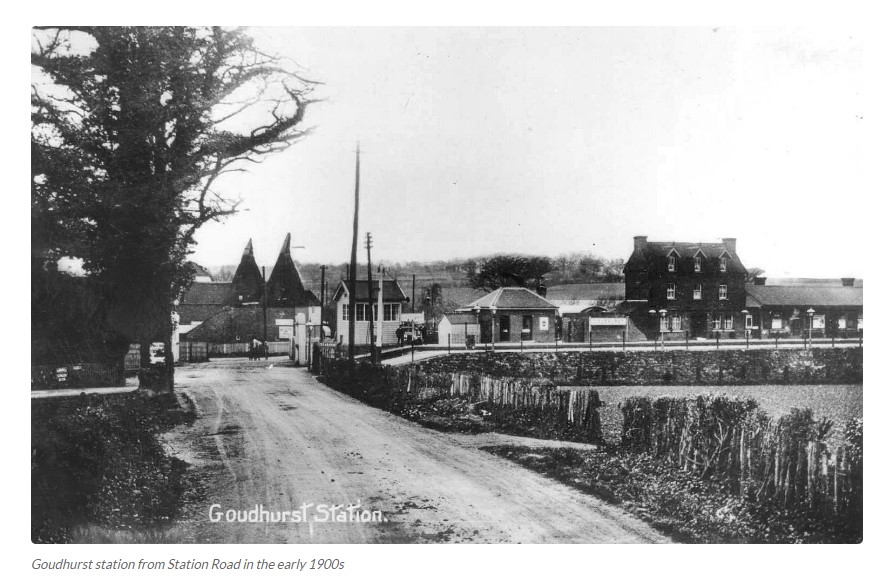

Billy Ripper - "On Fridays Dad would come and stay and give Mum a hand. Saturday or Sunday he would walk up to town to have a few beers in The Vine public house, or The Five Bells, with whoever had come down from Bermondsey. There was a sign at the pub doors firmly stating “No Gypsies”. Dad would come back and Mum would have cooked a roast dinner, which we would all tuck into. Later he would walk to Goudhurst Station to get the train home.

"Many a time we would all go for a walk at the weekend. Adults and kids would troop over past the Great Lake and the Mansion and go through Donkey Farm into Bedgebury Pinetum. Donkey Farm had the most enormous sweet blackberries which we would pick. The grounds of the Mansion had lots of Horse Chestnut (conker) trees, crab apples, hazel nuts and beech trees.

"The weekends were more or less a booze up at ’The Vine’ in Goudhurst, so all the men walked up to the town while the women got the dinner ready. On the way back they had to pass the ’the haunted house’ via a footpath that ran alongside it where the ghost of a white lady was supposed to wander. Everyone was a bit lightheaded and there was some banter about people disappearing along the path. One of the party, can’t remember for sure who it was but could have been Johnny Martin, stopped to relieve himself and didn’t arrive at the farm for dinner.  Naturally the imaginations worked overtime as to his disappearance and a search party was sent to find him. Despite the going back to the last place he was seen, he couldn’t be found. The view was he had gone back to The Vine or lost his way. Searching alternative routes to the farm through hop fields was unsuccessful but after a few hours Johnny turned up at the farm. Evidently after relieving himself had fallen into a ditch and the drink brought on sleepiness to which he succumbed. Naturally the imaginations worked overtime as to his disappearance and a search party was sent to find him. Despite the going back to the last place he was seen, he couldn’t be found. The view was he had gone back to The Vine or lost his way. Searching alternative routes to the farm through hop fields was unsuccessful but after a few hours Johnny turned up at the farm. Evidently after relieving himself had fallen into a ditch and the drink brought on sleepiness to which he succumbed.

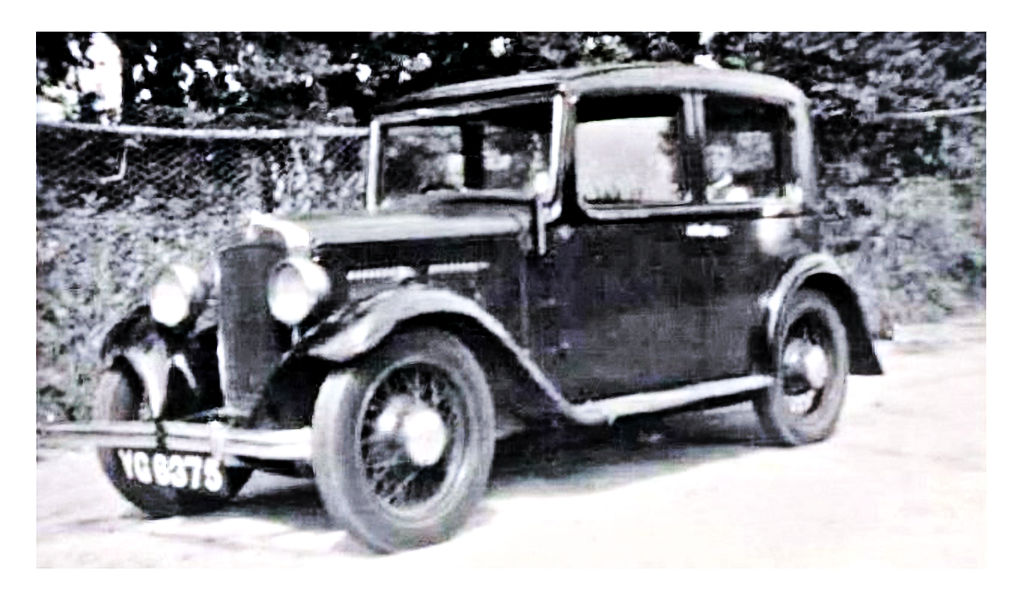

"When we came down in the car Dad would drive to the Vine and all the men were already there. When it was time to leave it was decided to all go back in the car. It was only a four seater but 10 all managed to squeeze in, The approach to the farm was a very steep loose gravel hill having the name 'Shitty Hill’ (I don’t know why). When they got to the bottom Dad made everyone get out and walk up the hill much to their annoyance. I think he had visions of being overloaded and breaking down. Of course when he got to the huts everyone wanted to know where the others were and he just said that they preferred to walk.

"One of our highlights was the concert. Doctors (students I guess) and nurses would set up a marquee and you could go there if you had any ailments. But in the evening they would have a concert playing instruments and we would sing all the old favourites of that time and my favourite was always “There’s a Hole in my Bucket Dear Liza” which could go on forever.  The adults would sing 'Little Brown Jug’, ‘Down at the Ol' Bull and Bush’, 'My Ol' Man Said Follow the Band’, and some other songs from the old time musicals. Wonderful time. The adults would sing 'Little Brown Jug’, ‘Down at the Ol' Bull and Bush’, 'My Ol' Man Said Follow the Band’, and some other songs from the old time musicals. Wonderful time.

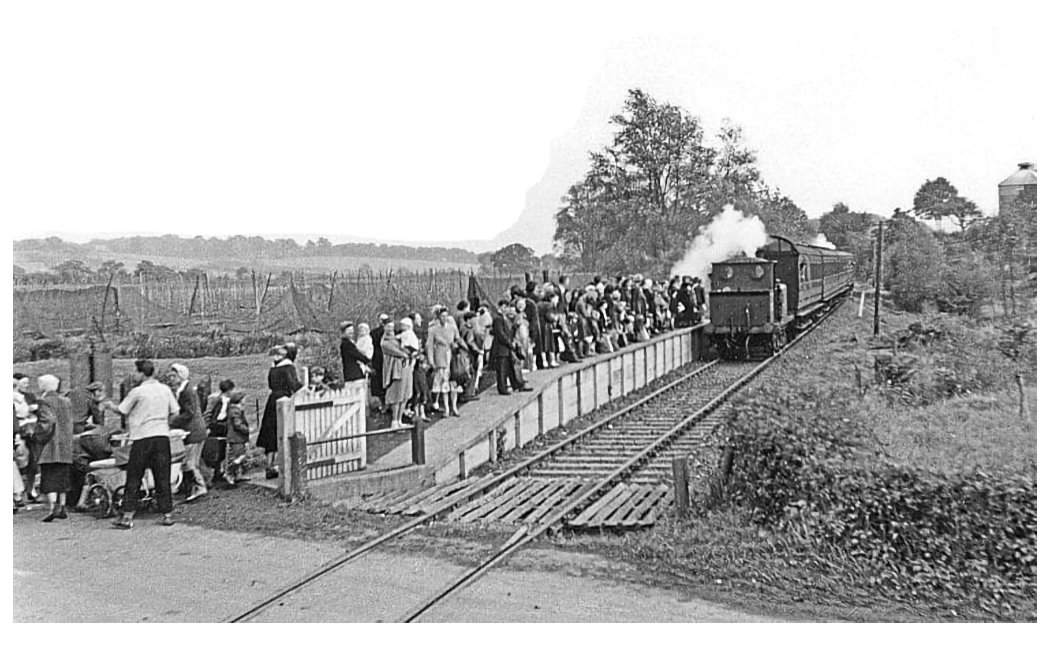

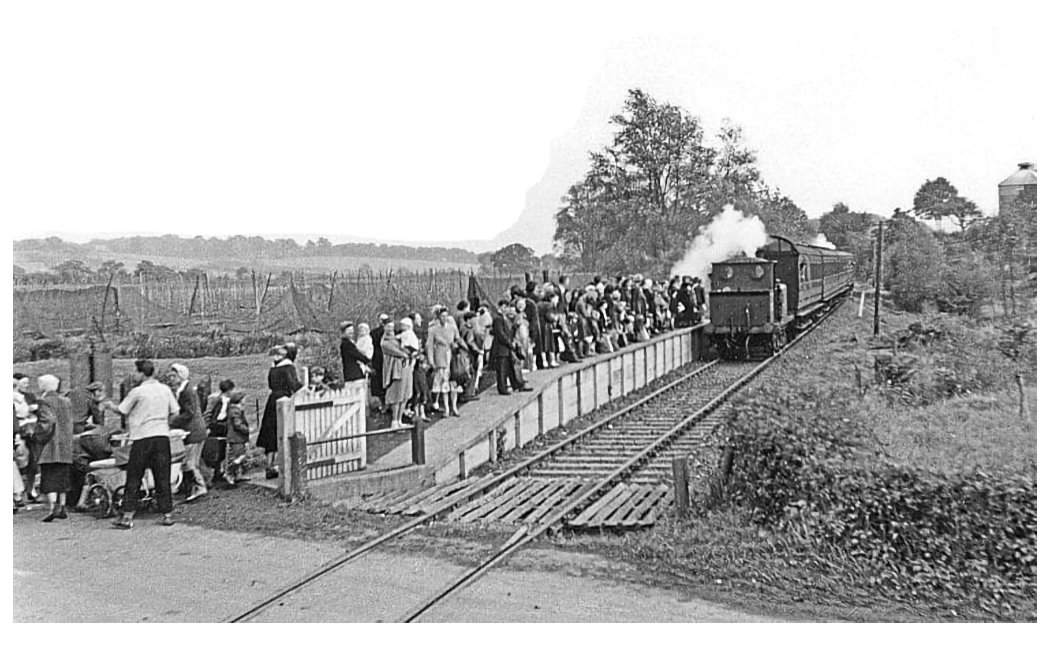

"And so it continued until the harvest was complete. At the end of ‘opping there would be a bonfire and music on the meadow where we would cook apples or potatoes on a stick and all the young girls and blokes would enjoy going their separate ways with a bit of canoodling before they got back to Bermondsey, where most people came from. Mum and I went home, not much richer, but it was a working holiday for her and wonderful time for me. [Click on this image to see hop pickers from near Bodiam waiting for their train back to London Bridge Station. A typical scene at many stations at the end of the season. The fully picked hop gardens can be seen behind the station.]

"By the mid-1950s hop picking had been mechanised and, although this meant there was less work, a holiday was still taken at this time. "By the mid-1950s hop picking had been mechanised and, although this meant there was less work, a holiday was still taken at this time.

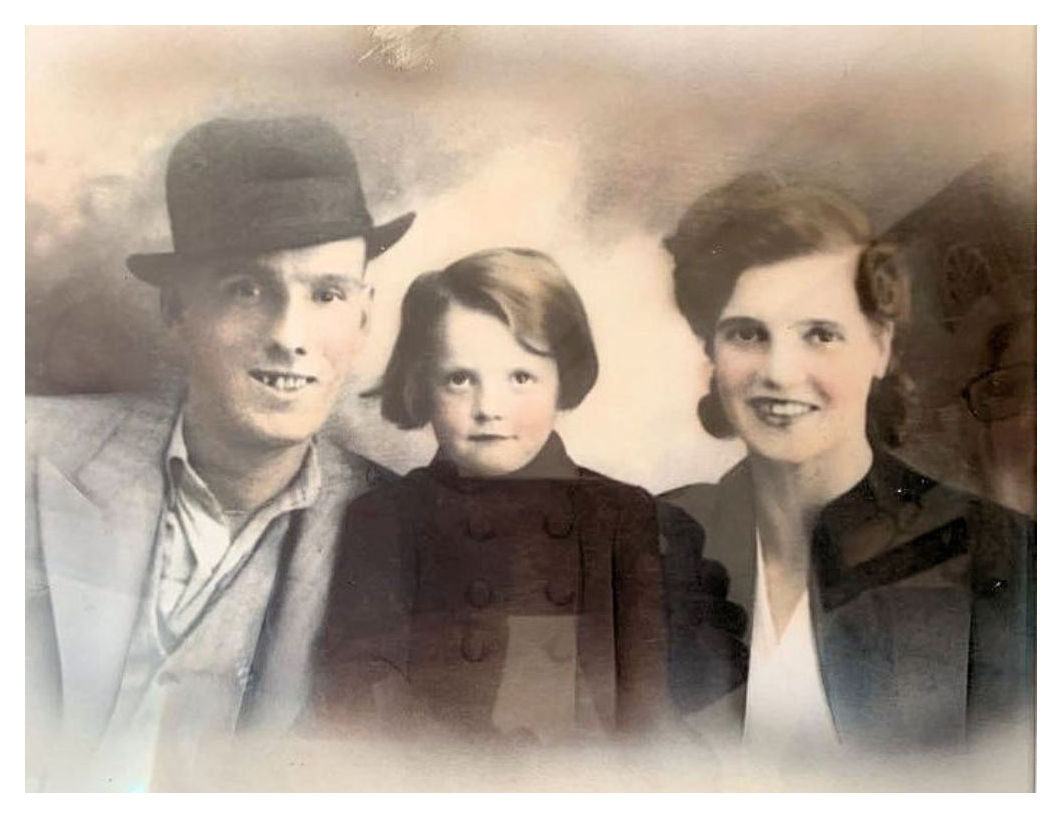

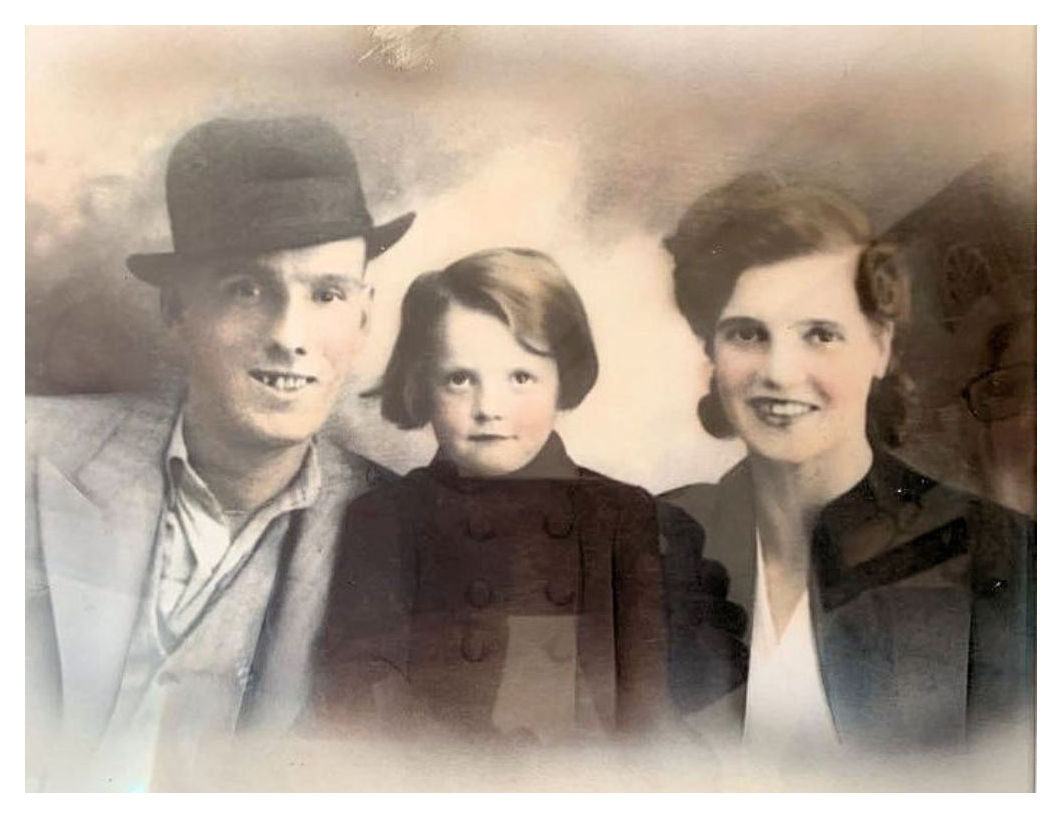

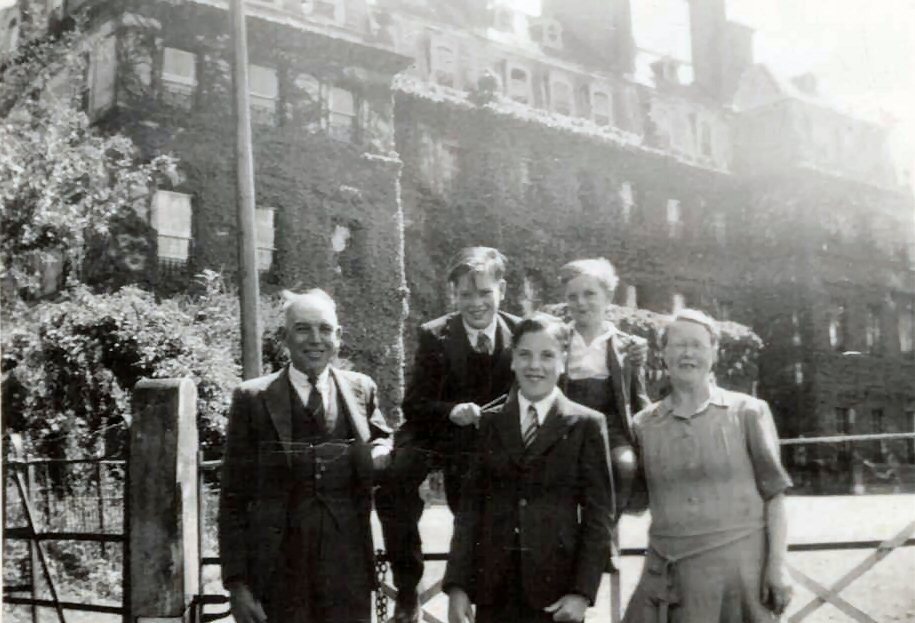

Florrie (pictured here with husband John Martin and daughter, Maureen) kept a hut at the farm and her daughter still did hop harvesting until around 1970. Florrie's grandson, Martin, can recall his times spent at Three Chmineys farm in the 1960s."

|

My father-in-law gave us the money for the coach fare."

My father-in-law gave us the money for the coach fare."

On one occasion we got as far as Sevenoaks, I think it was, when the lorry (not sure if it was the Bedford or the Austin) spluttered to a halt in clouds of smoke. His language made the smoke blue, in keeping with the colour of the lorry. It turned out that the engine had seized up. Off he went with Albert and had to buy another lorry. After a couple of hours he came back with an Albion (I think). Everything had to be transferred over and fortunately it didn’t rain. Of course he and Albert had to go back and tow the broken down lorry back to the yard. It was a long day for him and Albert and he vowed never to take anyone ‘opping again. But of course he did.

On one occasion we got as far as Sevenoaks, I think it was, when the lorry (not sure if it was the Bedford or the Austin) spluttered to a halt in clouds of smoke. His language made the smoke blue, in keeping with the colour of the lorry. It turned out that the engine had seized up. Off he went with Albert and had to buy another lorry. After a couple of hours he came back with an Albion (I think). Everything had to be transferred over and fortunately it didn’t rain. Of course he and Albert had to go back and tow the broken down lorry back to the yard. It was a long day for him and Albert and he vowed never to take anyone ‘opping again. But of course he did.

Dad’s bike got a puncture and they couldn’t fix it so Dad wheeled the bike back and Uncle Ron went on, on his own.

Dad’s bike got a puncture and they couldn’t fix it so Dad wheeled the bike back and Uncle Ron went on, on his own.